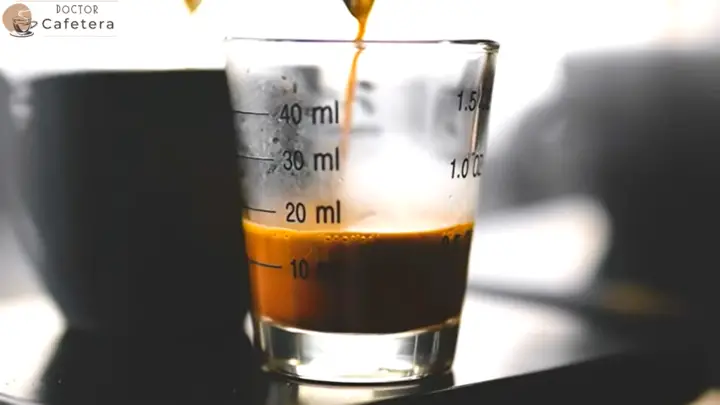

The crema has long been an indicator of espresso quality. A correct crema determined whether the barista was competent and whether factors such as grind setting, pressure, or temperature were correct. The crema itself was what people used to understand or assume that espresso was of quality.

However, there are not many specific books or studies focused on espresso crema, so this belief that a good crema is indicative of a good espresso is based more on tradition than science. Most of the articles you will find on the internet are repetitions in terms of information.

My goal with this article is, on the one hand, to summarize what we know today about crema formation and stabilization. And on the other hand, to speculate on crema’s role today. Is crema synonymous with quality in an espresso? Is it important, or can we leave it out?

What is espresso crema?

Crema is the Italian word originally used to define the foam on top of the espresso.

But how and why is this crema formed? The truth is that espresso is an incredibly complex drink, more so than any other.

During the preparation of espresso, 3 things happen that cause the crema to form:

- An emulsion of oils. When the hot water passes under pressure through the ground coffee bean, it extracts oils in the form of emulsified bubbles less than 10 microns in diameter.

- A suspension of solids. Fragments of the coffee bean’s cell wall pass through the filter during extraction. These pieces of the cell wall are up to 2 microns in size.

- An effervescence of gases.

Espresso is a complex tripartite coffee beverage with emulsified oils, suspended solids, and effervescent gases.

Espresso foam – also known by the Italian term crema – is itself a two-phase system composed of gas globules framed within liquid films (called laminae) made up of an aqueous solution of surfactants. These films tend to settle in a two-layer configuration of surfactant molecules facing the gas, with water molecules between them. The high molecular strength of the film allows its peculiar geometry: a bubble if isolated or a honeycomb structure of many bubbles growing together.

Espresso Coffee: The Science of Quality, edited by Andrea Illy, Rinantonio Viani

Illy and Viani’s definition speaks of “an aqueous solution of surfactants”. However, we are not 100% sure what these surfactants are, although we know that this is what stabilizes the cream.

Process of crema formation

Once the ground coffee is in the filter holder and we begin to pass water through it, the first phase of espresso preparation takes place. The water begins to draw the coffee into the cup, the beginning of the creation of the crema in the form of a liquid foam full of bubbles.

As we extract more coffee, this initial liquid foam begins to settle, giving rise to a dry polyhedral foam, where “surfactants” hold that surface area together.

Over time the surfactants fade, and the crema dissipates, leaving a sort of crust around the rim of the cup. This residue is incredibly bitter and ashy tasting, as it contains a large amount of the solids from the cell wall of the coffee bean.

Components of the espresso crema

When I spoke above about the 3 factors that caused the crema to form, I referred to a “gas effervescence”. The crema is full of gas, which gives it that spongy texture and, in particular, CO2.

Note: I am sure some of you may say this is not proven, and you would be right. Technically there are not enough studies regarding the components of espresso foam.

However, we have a great deal of research regarding foaming with carbon in soft drinks, beer, and the like.

But when it comes to espresso, there is hardly any research, so much of the knowledge that circulates is based on speculation. In any case, there is enough knowledge to assume that carbon dioxide is what fills the crema layer of espresso.

Of course, we have other things in the crema, including acids, fats, proteins, cell wall fragments, surfactants, etc.

Espresso crema formation process

- The first thing we have is the formation of bubbles, which occurs with the pressure of the water column passing through the coffee pod. You could say that the CO2 comes from the coffee and into our liquid solution.

- Then we have the rise of the bubbles, which, like in a beer, you have those bubbles gradually rising to the surface.

- When a little bit of time passes, the crema layer stabilizes on the surface of the espresso.

- Finally, there is a collapse of the crema, with traces of it sticking around the rim of the cup.

Traditional espresso

When people talk about traditional espresso, they always refer to the 9-bar espresso; however, the nine-bar espresso is not the first and original espresso.

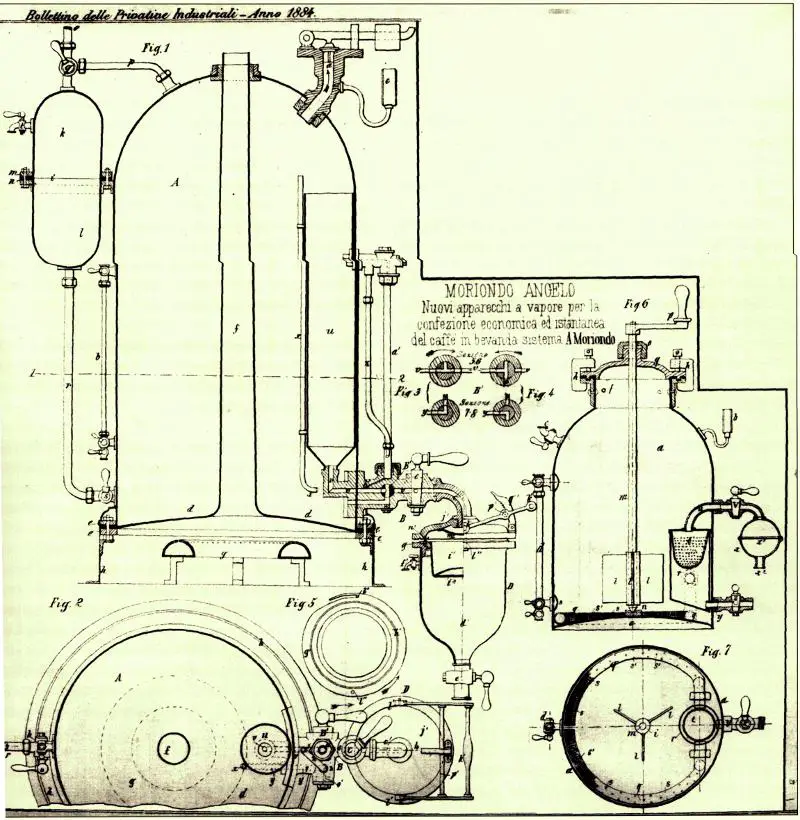

At the end of the 19th century, the first espressos were made with steam pressure, from one to one and a half bars of pressure. It was in 1884 when Angel Moriondo patented the first espresso machine, although it is believed that before this patent, this type of espresso was already being prepared with steam pressure.

Later, at the beginning of the 20th century, the steam espresso machine was improved, achieving up to 2 bars of pressure. But it was not until the middle of the 20th century that espresso changed radically, becoming what we know today as the true traditional espresso.

Gaggia espresso

In 1938, Giovanni Achille Gaggia patented the lever espresso machine, which finally made it possible to create nine bars of pressure. At this point, a stabilized foam began to be obtained at the top of the espresso, and this is where espresso changed forever.

For almost a hundred years, espressos had already been created; however, those first espressos differed greatly from today’s espresso. This is why the espresso of 1948 is what we consider traditional today.

Over the years, the definition and tradition of espresso have changed, and the definition and tradition of espresso dating back to 1948 have changed, forgetting the previous years. This is not a bad thing, but it should be clear that the crema started with espresso in the mid-20th century.

Is crema really important in an espresso?

I think there has been a misconception about crema for many years; there is a dogmatic view that relates the crema’s quality to the espresso’s quality. It is time to relax that view and understand that espresso can be delicious with little crema, a lot of crema, or no crema at all.

There has been too much of a push towards a specific espresso style for so long that now is the time to subvert that and get back to the roots of espresso. It’s time for us to experiment with extraction and not worry about crema.

Just think that espresso was born with just a bar and a half of pressure, then it went up to 9; after that, we experimented with pre-infusion and lowering the pressure. For all these reasons, when preparing espresso, we have to have fun and investigate without worrying about the crema.

How to get more crema in espresso?

You should not worry about crema, but if you like crema, all you need to know is that you should get a very dark roast coffee, and you will get as much crema as you want.

As for the type of bean, no study claims that Robusta beans create more crema than Arabica beans. So don’t get stuck on getting only Robusta; you can play around with making crema with any coffee bean you want. But keep in mind that fresh dark roasted coffee is the one that will give you more crema.

You may be interested in: